“Every man looked like a soldier, while inflexible determination was depicted upon every countenance.”

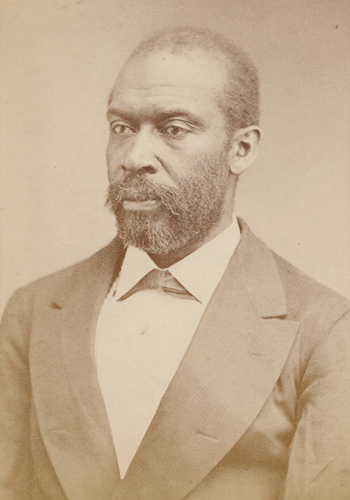

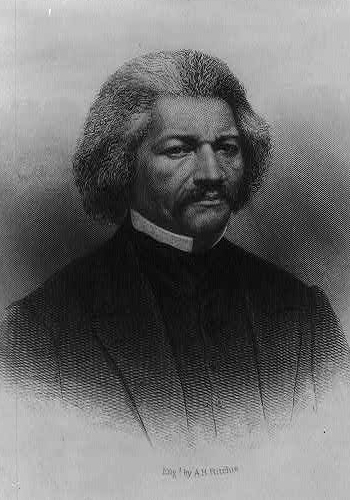

— Thomas Morris Chester (pictured above), African American lawyer, soldier, and war correspondent during the Civil War, on the bravery and patriotism of Black servicemembers

Essential Question

How did journalists report on slavery and military conflict during the Civil War?

Overview

The Civil War cost the lives of approximately 750,000 soldiers and led to an end to legal slavery in the United States. Nearly every civilian was connected to the war in some way through friends, family, or personal experience. Newspaper editors and publishers knew this was the biggest story of the century and wanted to make sure the public knew all about it.

On the eve of the Civil War, there were approximately four thousand periodicals in the United States, twice as many as in Great Britain. Most were small weeklies, but nearly all communities had at least two newspapers. Larger cities had four or five; some of them were published daily.

The rise of the so-called “penny press” enabled working-class Americans to buy cheap publications. Newspapers were filled with reports from the battlefields, commentary from government officials, and the occasional editorial from the editor or publisher.

Context

By the 1830s, journalism was becoming a major force in America. As literacy increased, greater numbers of the public were craving news that informed and entertained, including the working class and immigrants. However, papers were still owned by white men and the vast majority served a white audience.

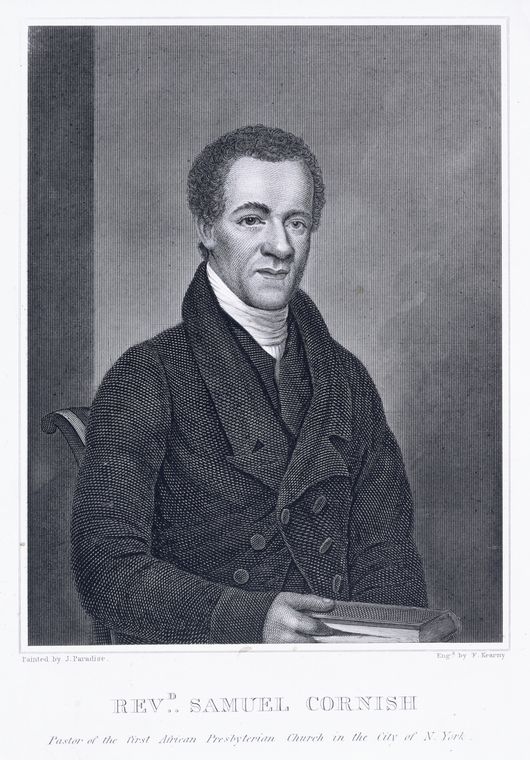

One of the first notable exceptions was Freedom’s Journal, the first African American newspaper in the United States, published weekly in New York City from 1827 to 1829. “We wish to plead our own cause,” coeditors John Brown Russwurm and Samuel Cornish wrote in their first issue, adding that, “Too long have others spoken for us. Too long has the public been deceived by misrepresentations, in things which concern us dearly.” By the start of the Civil War, around three dozen Black-owned papers had been established throughout the country.

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, organizations like the American Anti-Slavery Society worked to get out a different perspective by publishing weekly newspapers advocating for the abolition of slavery. Frederick Douglass, a frequent speaker for the Anti-Slavery Society, published his own newspaper in Rochester, New York, the North Star (1847–1851).

New technologies and new demands for information during the Civil War changed journalism in many ways. The telegraph, invented in 1844, allowed newspapers to gather information from different locales and report the news more quickly. This led to the development of the Associated Press, the first cooperative news-gathering organization in America. Steam engines also changed journalism by powering large presses that could print thousands of copies in an hour. Steam locomotive trains carried thousands of copies of the newspapers all across America.

Discuss the following questions:

- How accessible was print media news to Americans on the eve of the Civil War in terms of amount and price?

- Why were publications like Freedom’s Journal and North Star important in giving African Americans a voice in the debate over slavery and the purpose of the Civil War?

- How did new technologies during the Civil War impact journalism and the public’s knowledge of major events?

Journalists

The increased demand for news about the unfolding catastrophe modernized journalism practices. Reporters and photographers would travel with the soldiers, live in their camps, recount their battles in print, and report on their deaths.

Most reporters were teachers, lawyers, or small-town newspaper editors who knew how to write a solid story. But events moved quickly and because of that, many articles contained rumor, gossip, and sensationalism.

During the Civil War, nearly all journalists were white men. But there were exceptions. Frederick Douglass was born an enslaved person in Maryland in 1818, and after several attempts, escaped slavery in 1838. With money borrowed from friends he bought a printing press and published a weekly newspaper. He left Maryland and traveled north, where he became a leading abolitionist. After the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, he expanded the paper’s editorializing to women’s suffrage.

Thomas Morris Chester, the only Black war correspondent for a major daily paper, reported on the frontlines for the Philadelphia Press. Chester, the son of two abolitionists, worked as an army recruiter for the Fifty-Fifth Massachusetts Colored Regiment at the start of the war. In 1864, he traveled with the Army of the Potomac and reported on the siege of Richmond, Virginia, by Union soldiers.

Though not primarily known as a journalist, Harriet Jacobs wrote for abolitionist publications such as the National Anti-Slavery Standard and The Liberator. Jacobs was born in North Carolina and escaped to the North as an adult. Her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, was originally partially released as a serial in the New-York Tribune, though the content was deemed too graphic for readers of the paper and so was ultimately published as a book.

Three young Quaker women published the Waterford News, a pro-Union newspaper inside Confederate Virginia, in 1864. Their goal was “to cheer the weary soldier, and render material aid to the sick and wounded.” Risking arrest or worse, the women raised almost a thousand dollars for the US Sanitary Commission, an organization providing medical care to Union troops.

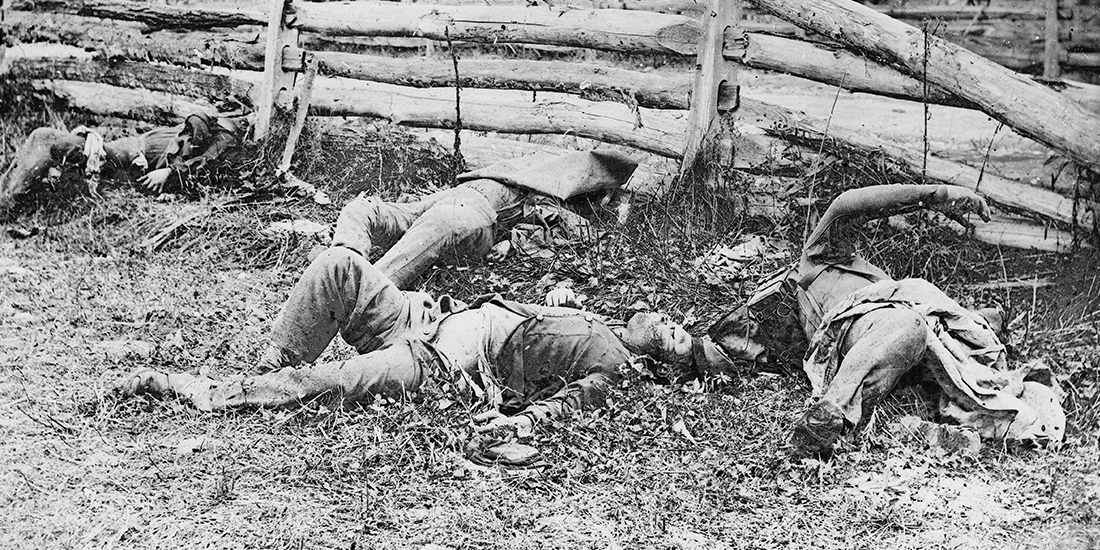

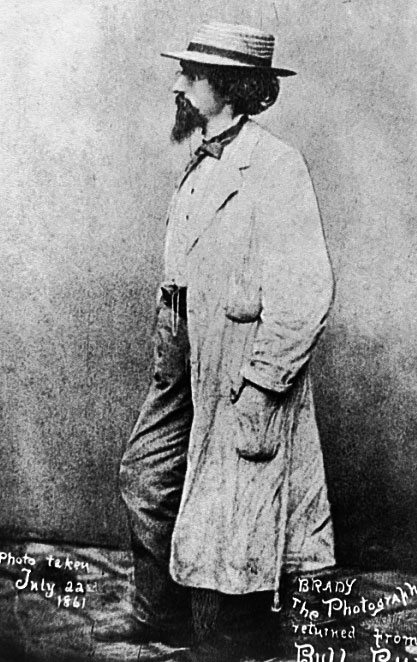

Photojournalists Alexander Gardner, Mathew Brady, and others brought the war home in graphic detail. They often traveled to the battlefields on horse-drawn wagons that carried their darkrooms allowing them to develop their photographs within minutes of taking them.

After an exhibition of Brady’s photos of the Battle of Antietam, the New York Times wrote, “Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it."

Discuss the following questions:

- How did journalists cover the Civil War and why did their reporting sometimes rely on rumor, gossip, and sensationalism?

- How might have African American journalists brought a different perspective reporting on the Civil War?

- Review the quote from the New York Times on Mathew Brady’s photos. What was the impact of such photographs of Civil War battle scenes on the American public?

News Formats

Professional journalism practices matured during the Civil War. Newspaper reporters worked in the field and sought out eyewitness descriptions. Publications were fiercely competitive, so getting a story out quickly and accurately became the goal. In their quest to convey what really happened, reporters resisted military and government censorship. All these principles would become standards for today’s journalism.

Illustrated weekly magazines grew in popularity. Magazines like Harper’s produced longer stories, often in serial form, with large woodcut illustrations and occasional photograph engravings printed in their pages.

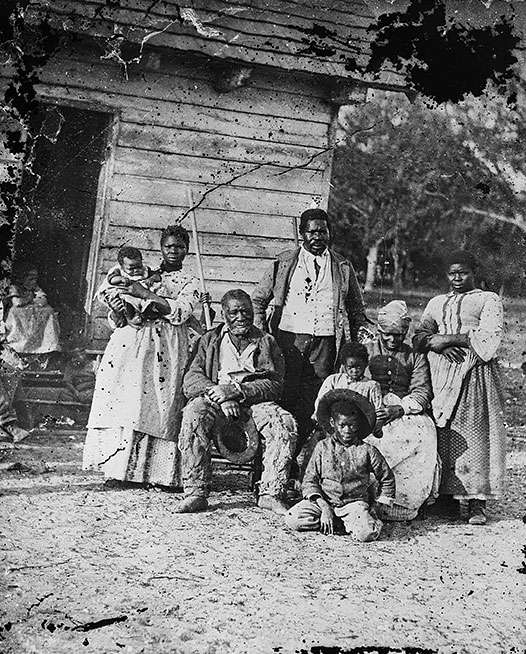

By the time of the Civil War, photography was in common use. However, technical limitations prevented newspapers and most magazines from directly printing photographs. Instead, etchings were made from photographs, then printed. Photographs of enslaved people, the dead, and destroyed cities stirred the emotions of nineteenth-century Americans.

Discuss the following questions:

- What were some of the standards of journalism that emerged during the Civil War?

- How could the mass production of weekly magazines with longer stories and illustrations bring the Civil War to the public?