Outcomes

A month after the New York World published Bly’s account of her experience in the asylum, a grand jury panel visited the facilities to investigate. The hospital staff was tipped off in advance and were ready. The staff brought in fresh food and scrubbed down the facilities. The asylum officials released or transferred many of the patients Bly had interviewed. The doctors denied Bly’s account of the experience.

Despite all this, the grand jury agreed with Bly and submitted a report to the city government. After reading the report, officials fired abusive staff members and set new sanitation codes. To better meet the needs of individual patients, multilingual support staff were hired to assist immigrant patients and their families. New examination procedures were established so that only the seriously ill were committed to the asylum.

In addition, the city government passed an $850,000 budget increase to the Department of Public Charities and Corrections for continued improvements. Measures to increase the budget were already underway through the work of politicians and advocacy groups, but Bly’s piece helped to increase the amount and push passage of the budget along.

Since the 1830s, social reformers like Dorothea Dix had lobbied state lawmakers to build new facilities to care for the mentally ill, which focused on moral treatment of patients and the removal of straitjackets and shackles. Dix’s efforts, in particular, resulted in the construction of state psychiatric institutions across the country.

Bryce Hospital, opened in 1861 in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, is the state’s oldest and largest inpatient psychiatric facility. Carol M. Highsmith, photographer, 2010. Library of Congress

As is often the case with large institutions, state mental hospitals began to run into some of the same problems that Dix had set out to fight in the first place, including poor treatment of patients, in part due to a lack of medical understanding of mental health at the time as well as a lack of oversight when staff inside hospitals carried out gross injustices on their patients.

Discuss the following questions:

- What changes did officials in New York City make after Nellie Bly’s reporting on asylums?

- What did Dorothea Dix feel was needed to reform state mental health institutions? Why might government-run institutions be better than private ones? What might be some of the downsides to government-run institutions?

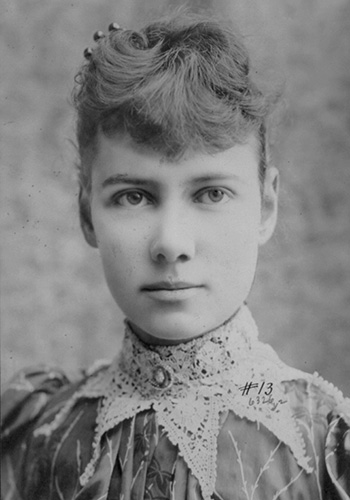

Stephanie McIver, PhD, counseling director at the University of New Mexico. Permission has been granted for educational purposes only courtesy of The University of New Mexico.

Challenges Continue

While some improvements were made inside mental hospitals at the turn of the nineteenth century due to Bly’s investigation and activists’ work, serious issues peaked again and were once more exposed in the 1950s. Since then, new drug treatments, increased access to counseling, and a greater societal understanding of mental health issues have occurred, leading to the closing of many state-run psychiatric institutions. State budget cuts also contributed to hospital closures.

The role of state-run psychiatric institutions in the field of mental health remains a contentious part of American history—the way facilities were operated as well as their many closures. Some families and medical health professionals argue there is a need for such facilities and that so many closures were a mistake. At the same time, stories of poor treatment by patients continue to appear in the news, a reminder of the grim past of those with mental health issues in America. Health disclosure laws today make stories like Bly’s much more unlikely, but journalists continue to track mental health in the United States, sometimes from innovative perspectives.

Dr. Stephanie McIver, head of counseling at the University of New Mexico, supports young people and also works on educating the public about mental health challenges facing African Americans. Congress relies on experts like McIver to craft new laws that support mental health services.

Investigations into mental health support in the country are often undertaken by public officials and legislators. In 2019, Rep. Joyce Beatty of Ohio spoke on the House floor about the lack of mental health funding for Black Americans. Like Dorothea Dix, Beatty traveled across the country speaking with Black community members about the disparities in health care. In her floor speech, Beatty addressed the lack of access to treatment and the stigma of mental health within Black communities. If you would like to know what bills members of Congress are working on, visit Congress.gov and put your topic into the search bar.