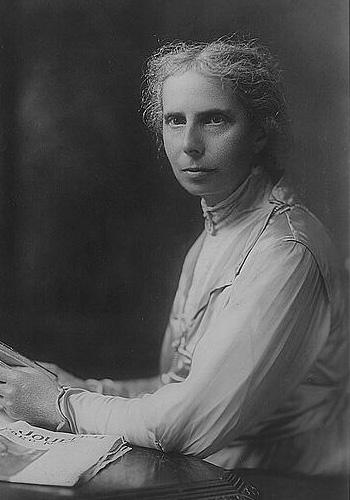

"Justice is better than chivalry if we cannot have both."

—Alice Stone Blackwell, journalist and editor, on the matter of a woman’s right to vote

New York City Suffragist Parade. May 4, 1912. American Press Association. Library of Congress

Essential Question

How did journalists cover the movements for women’s suffrage?

Overview

On June 4, 1919, the United States Senate approved the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, granting women the right to vote. Three-quarters, or thirty-six of the forty-eight states in the union, were required to ratify the amendment. In the final push for women’s suffrage, strategies combined lobbying Congress with pickets, parades, demonstrations, arrests, hunger strikes, and other “militant” tactics throughout the country and in Washington, DC.

Throughout the country, citizens were split on the advantages and perceived disadvantages of women’s suffrage, and journalists highlighted these arguments in editorials, cartoons, and front-page coverage. You will observe the techniques they used and explore the story of ratification as it unfolded in your own state.

NEW: A supplementary vocabulary guide (Google doc) is now available for this case study. PDF version here.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony some decades after they first met. c. 1880–1902. Library of Congress

Context

Ratification was the result of many decades of activism by suffragists, dating back to the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments in 1848, modeled on the language of the Declaration of Independence. While Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, two of the main convention organizers, went on to become leaders in the suffrage movement, men and women in every state engaged in setting up conventions, lobbying, picketing, parading, and civil disobedience.

The first strategy used to obtain votes for women was to tie the issue to the Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment, adopted in 1868, which guaranteed the basic rights of citizens. Just a few years later, Susan B. Anthony was arrested in Rochester for voting in the 1872 election and stood trial. Anthony made sure the proceedings would be highly public and circulated her closing remarks in newspapers throughout New York State.

The strategy connecting women’s suffrage to the Fourteenth Amendment failed. It was replaced by new tactics by the National American Woman Suffrage Association under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt. After years of lobbying lawmakers, large-scale protests, and coverage by the press, the US Senate approved the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution on June 4, 1919. It states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Discuss the following questions:

- What was the initial event that launched the suffrage movement?

- The Fourteenth Amendment states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof; are citizens of the United States and the state wherein they reside.” How was the right for women to vote tied to this amendment?

- What were the tactics the women’s suffrage movement used to get the US Senate to approve the Nineteenth Amendment?

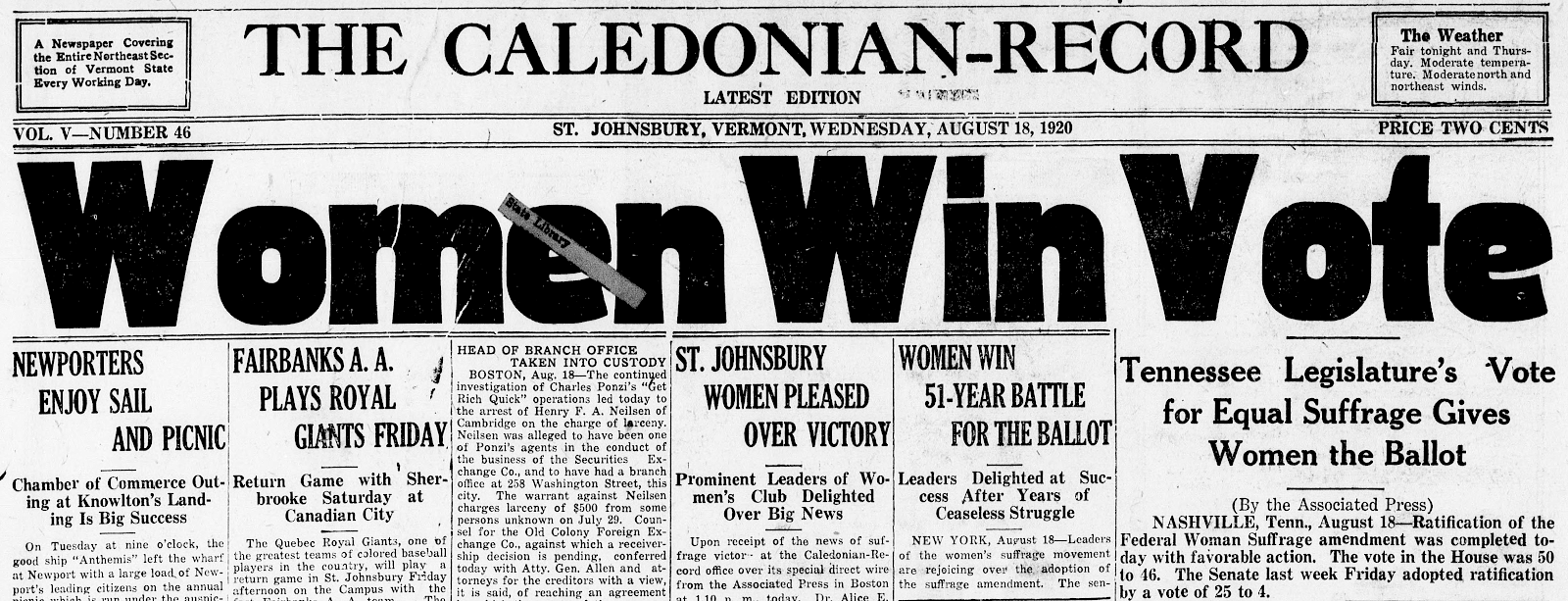

As stipulated in the Constitution, the amendment was now sent out for ratification in the states, where approval by three-quarters, or thirty-six of the forty-eight states, was required for it to become law. On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the thirty-sixth state to ratify the amendment, with a single tie-breaking vote by twenty-four-year old legislator Harry Burn, who clutched in his hand a letter of support for the amendment from his mother, which had changed his initial opposition to women’s suffrage.

Headline in the Caledonian-Record. St. Johnsbury, Vermont, Aug. 18, 1920. Library of Congress

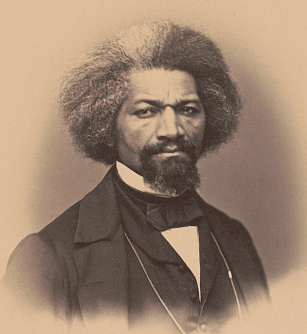

Frederick Douglass, 1862. Library of Congress

Journalists

In 1848, Frederick Douglass, editor of the North Star and well-known abolitionist, spoke at the Seneca Falls Convention and wrote articles covering the women’s suffrage movement. In 1866, Douglass, along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, founded the American Equal Rights Association, which called for universal suffrage for African Americans and women.

The association disbanded just a few years later due to rising tensions over whether to withhold support for the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, since they omitted women. Douglass remained influential in both movements until his death in 1895, but at the time he said, “the cause of the negro [was] more pressing” than that of women’s.

Alice Stone Blackwell with a copy of Woman’s Journal. Library of Congress

While another well-known suffrage pioneer, Lucy Stone, disagreed with Douglass’s sentiment, she agreed that Black male suffrage should come first. In 1870, Stone and her husband, Henry Browne Blackwell, founded the weekly paper Woman’s Journal in Boston, which soon became the unofficial and then official voice of the suffrage movement. The couple’s daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, worked as one of the Journal’s writers and later editor. As passage of the Nineteenth Amendment neared, suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt said of the paper, “The suffrage success of to-day is not conceivable without the Woman's Journal's part in it.”

Similar to other parts of the nation, the women’s rights movement in New England rose out of efforts to abolish slavery. Like her mother, Alice Stone Blackwell lectured on rights for African Americans and women at a time when a woman lecturing in public was considered indecent.

Despite their efforts toward equality, suffrage leaders, predominantly white women, didn’t always make Black women feel welcome in the movement. They feared doing so would cause them to lose support from southern white women. However, this didn’t stop Black women from playing key roles as suffrage leaders and starting Black suffrage organizations.

The Broad Ax. Salt Lake City, Utah. July 14, 1917. Library of Congress

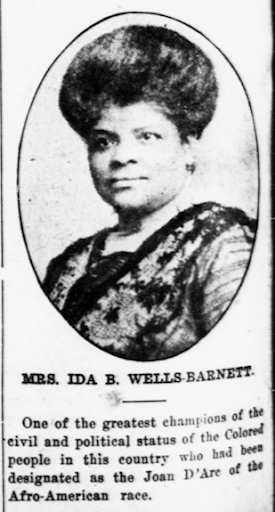

Ida B. Wells, a Black journalist and civil rights activist, started the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago in 1913. Prior to her work in the suffrage movement, Wells’s investigative reporting on the horrors of lynching had already made her an internationally known and influential leader. She co-owned the Free Speech of Memphis, the Conservator and the Broad Ax and was a cofounder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

On March 3, 1913, the day before the inauguration of President Wilson, Wells and other members of the Alpha Suffrage Club were prepared to march in the women’s suffrage parade in Washington, DC. The group was instructed to march with the rest of the Black suffragists at the rear of the parade. Wells rebuked this directive and joined the front of her state’s delegation. Her defiant actions were highly publicized throughout the country.

Discuss the following questions:

- What was the partnership like between Frederick Douglass and women’s suffrage movement leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony? Why did this partnership soon break up?

- How did the Woman’s Journal weekly publication help promote the Nineteenth Amendment?

- Why did suffrage leaders not welcome Black women to the movement? How did Black women respond to this snub and what actions did they take on their own?

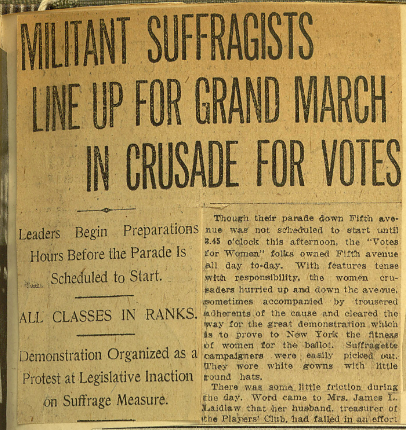

"Militant Suffragists Line Up for Grand March in Crusade for Votes.” New York. May 6, 1911. Library of Congress

News Formats

At the start, few newspapers covered the Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. However, as word spread about the stirring speeches made by organizer Elizabeth Cady Stanton along with Frederick Douglass, positive coverage picked up. And yet the press was largely unsympathetic toward the state conventions that followed, in which hecklers and groups disrupted meetings while lectures were taking place.

Newspaper readership in the early twentieth century was remarkably high. The media reported on news stories in several states that had passed their own suffrage laws, and large-scale protest parades in New York in 1912 and in Washington, DC, in 1913 caught the media’s attention. The ratification process, which took place between 1919 and 1920, provided each state with a rich source of local and national news. Magazines like Harper’s Weekly and Puck featured stories on suffragists and a series of clever political cartoons.

Discuss the following questions:

- How did newspapers of the time report on the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848? Why do you think they chose to report this way?

- How did the change in momentum in favor of women’s suffrage and the tactics of the movement increase the press’s coverage of the suffrage movement?

More than four million women had voting rights—all in the West—equal to men in eleven states by the end of 1914, leaving women elsewhere still reaching for the light of Liberty's torch of freedom. Puck magazine. Feb. 20, 1915. Library of Congress