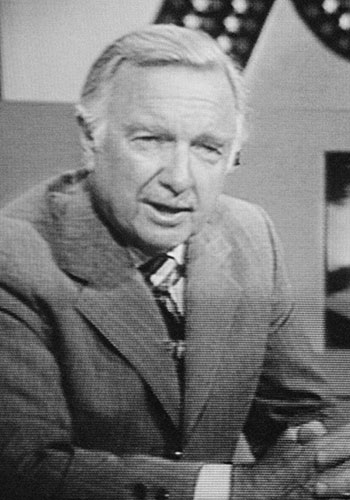

“Journalism is what we need to make democracy work.”

—Walter Cronkite, broadcast journalist

Essential Question

How did journalism help tell the story of the Vietnam War?

Overview

At the end of World War II, the United States emerged as the world’s economic powerhouse while many European countries struggled to rebuild at home and reassert authority in colonies and client states around the world. In 1954, France lost control of its former colony in Vietnam and the US stepped in to try and prevent the small country from slipping under Communist influence, at first with military supplies and advisers, then with ground troops.

The decision would lead to years of guerrilla warfare with seemingly no victory in sight for America or its allies in South Vietnam. In 1973, President Richard Nixon signed the Paris Peace Accords, with the promise of ending direct US involvement in the Vietnam War; however, fighting continued until Saigon fell to North Vietnamese Communist forces in 1975.

At the war’s end, two million Vietnamese civilians and tens of thousands of people in Laos and Cambodia had been killed. The military death toll included 58,000 American troops; 250,000 South Vietnamese troops; and more than 1 million North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops. Viewers tuned in nightly in the United States to try and understand what was happening a world away. Many had family members serving in the war, and between video footage of the aftermath of battle and the changing role of news media in covering war, many Americans became increasingly concerned about America’s role in Vietnam as the fighting continued.

Long Khanh Province, Republic of Vietnam. SP4 R. Richter, 4th Battalion, 503rd Infantry, 173rd Airborne Brigade (left) and Sergeant Daniel E. Spencer (right), waiting near their fallen comrade. National Archives

Coretta Scott King holding a candle and leading a march at night to the White House as part of the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, which took place on October 15, 1969. Library of Congress

Context

Up until the mid-1960s, much of the reporting on the Vietnam War was supportive of the war effort. Many Americans believed their soldiers were defending Vietnam from Communist aggression, including from China or the Soviet Union. By the late 1960s, however, reports of the war showed that the US was not making progress, and some Americans began to question US motives and involvement altogether.

In response, several political officials and even average Americans accused the media of undermining the war effort. Some called on Congress to reduce press freedoms. Americans who criticized the war were called unpatriotic and told to “love it or leave it.” A strong antiwar movement began to build up as a result of this pushback.

Discuss the following questions:

- Why did the United States become involved in Vietnam?

- Why did Americans’ feelings about US involvement in the war change by the late 1960s?

- Why do you think some Americans reacted negatively to the press reporting on the Vietnam War?

The Pentagon Papers

The controversy over the Vietnam conflict came to a dramatic climax with the 1971 leak of secret government documents known as the Pentagon Papers. The Department of Defense had commissioned a report on the history of the United States’ political and military involvement in Vietnam. The forty-seven-volume report revealed that the government had systematically lied, not only to the public, but to Congress, about the size, scope, and direction of the war.

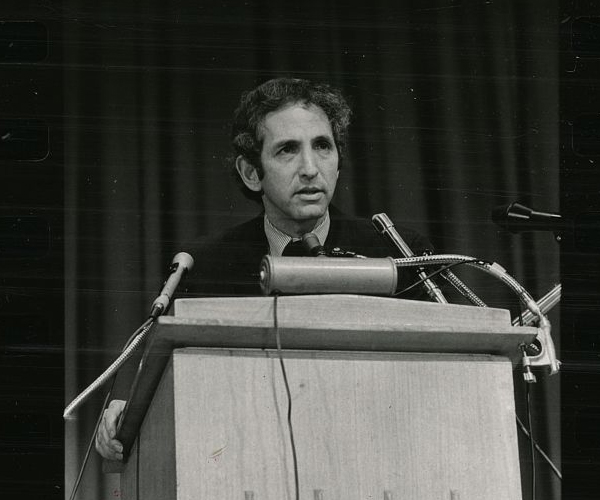

Daniel Ellsberg, originally an ardent supporter of the war, had worked on the report. He became deeply opposed to the war after the report was completed and decided to leak portions of it to the press in 1971. When the New York Times published the first of a series of articles, the Nixon administration claimed it was a threat to national security and sued to stop publication. The Supreme Court took up the case and rejected the government’s claim in a landmark First Amendment decision, New York Times Company vs. United States.

Daniel Ellsberg, speaking at a press conference in New York City in 1976. Library of Congress

Discuss the following questions:

- How did the Pentagon Papers reveal the government’s deception in how it was conducting the war?

- Why do you think the Supreme Court rejected the Nixon Administration’s claim that publishing the Pentagon Papers was a threat to national security?

Professor Bernard Fall of Howard University (left) and journalists David Halbertstam (center) and Neil Sheehan (right) on WGBH’s National Education Television, “At Issue; The Stakes in Vietnam.” April 20, 1964. Permission has been granted for educational purposes only, courtesy of American Archive of Public Broadcasting (WGBH and the Library of Congress).

Journalists

For the most part, Vietnam War journalists had access to ground soldiers, high-ranking officers, and battlefields. Journalists dug deep into military records and interviewed a broad range of personnel. Vietnam’s history, its culture, and its politics made this war different than any other Americans had fought.

David Halberstam was a Pulitzer-prize-winning journalist for the New York Times who wrote stories challenging the US government’s optimistic version of the war. Halberstam’s reporting on the South Vietnamese Army’s defeat at the battle at Ap Bac in 1963 earned him the disapproval of the Kennedy administration. President Kennedy made a personal appeal to the Times to replace him with a more agreeable journalist, but they refused.

Walter Cronkite was a veteran news reporter who had made a name for himself during World War II. In 1962, he took over the chair of the CBS Evening News, earning the moniker “The Most Trusted Man in America.” In his first six years as network news anchor during the Vietnam War, Cronkite reported on military operations, government policy, and body counts. In early February 1968, after the Tet Offensive, he traveled to Vietnam to get a firsthand look at the war. He returned a week later and offered a rare editorial to his viewers that wasn’t in support of the war.

Walter Cronkite and a CBS crew interviewing the commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, during the Battle of Hue City, Feb. 2, 1968, in Vietnam. National Archives

In it he said, “For it seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate,” adding, “that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could.”

Discuss the following questions:

- How did the extensive access to ground soldiers, officers, and battlefields that journalists enjoyed during the Vietnam War give them a good account of what was happening?

- Why was Walter Cronkite’s commentary suggesting the Vietnam War end in a stalemate so shocking to many Americans?

Wallace Terry, a news correspondent in Vietnam for Time Magazine, discussed what it was like to cover the war in a 2001 interview with PBS NewsHour’s Jim Lehrer. Permission has been granted for educational purposes only, courtesy of American Archive of Public Broadcasting (WGBH and Library of Congress).

Reporting Begins to Mirror Societal Change

Some of the ways the war was reported mirrored the social change occurring in America at the time. As the 1960s marked a period of liberation for many people of color and women, several female and African American news correspondents reported from the frontlines.

In 1967, at age twenty-four, Australian-born Kate Webb paid her own way to Saigon. Armed with a few hundred dollars and a Remington typewriter, she worked as a freelance reporter. During the 1968 Tet Offensive, Webb was the first news correspondent to reach the US Embassy while it was under attack. By 1971, she was working as bureau chief in Cambodia where she was captured by North Vietnamese forces. Erroneously reported to have been killed, Webb emerged from the Cambodian jungle after being held prisoner for twenty-three days.

A disproportionate number of minorities and low-income Americans fought in Vietnam, many of whom were sent to the frontlines and made the ultimate sacrifice. Known as the “First Lady of the Black Press,” Ethel Payne covered the war for the Chicago Defender, a prominent African American newspaper, where she reported on the duties of Black soldiers and sent messages back home from some of the troops.

Journalist Wallace Terry highlighted the stories of nine Black veterans in Bloods: An Oral History of the Vietnam War, which earned him a Pulitzer Prize nomination. Regarding his experience covering Vietnam for Time magazine, Terry told PBS NewsHour’s Jim Lehrer in 2001, “You take a descent into hell when you enter war.”

Discuss the following question:

- How might reporting from a female or journalist of color provide a different perspective on an event like a war compared to the dominant voices at the time?

News Format

In the early 1960s, the government claimed the conflict was a “police action” and the American media treated it that way. Coverage increased in 1963, with the death of then–South Vietnamese president Ngo Diem. Originally reported as a suicide, it was soon revealed he was assassinated by the South Vietnamese military. A later investigation determined it was done with the full knowledge of the United States government.

As military operations intensified, the number of journalists in Vietnam increased from a dozen in 1964 to over six hundred in 1968. News came from US wire services, radio, television, newspapers, and news magazines. The three commercial networks reported on the war every evening.

Remembering Vietnam exhibit. National Archives

The conflict in Vietnam became known as America’s first “television war.” From eight thousand miles away in the jungles of South Vietnam, journalists would shoot their film, file their reports, and have them published or broadcast on the next day’s news. All this was presented to the American public in living color.

Discuss the following questions:

- How did the way the American media cover the war change from the early 1960s to the end of the war?

- How did the increasing news coverage of the war deepen Americans’ interest?

- What impact do you think America’s first “television war” had on US citizens?