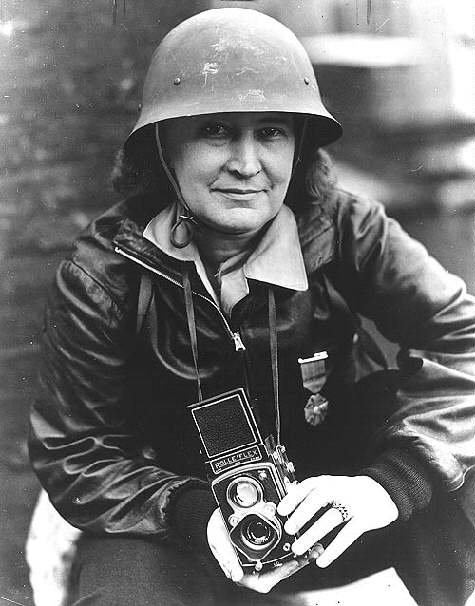

Thérèse Bonney wearing medal, Feb. 1942, New York World-Telegram & Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. Library of Congress.

"I go forth alone, try to get the truth and then bring it back and try to make others face it and do something about it."

—Thérèse Bonney, World War II photojournalist whose images of homeless children and adults in rural areas of Europe reached millions of readers in the United States and abroad

Essential Question

How did war correspondents break barriers, inform the home front, and challenge public perceptions during World War II?

Overview

During World War II, there was a tremendous shortage of workers in all sectors of American business and industry. Millions of men went off to fight in the war. Women were called upon to fill the vacant jobs in factories and businesses, and as war correspondents. Female journalists in print, photography, and radio made important contributions to the war effort by informing citizens at home and highlighting the human devastation of the conflict. Thérèse Bonney’s photography of the victims of the concentration camps in Germany and homeless women and children in rural areas were seen all over the world.

In this case study, you will:

1. Analyze the contributions of female journalists and other groundbreaking journalists during World War II.

2. Examine primary sources in the form of newspaper articles, political cartoons, photography, and radio transcripts and compare one of the challenges faced by women news correspondents during World War II to a modern-day issue.

Context

After World War I, United States leadership pushed for a “return to normalcy,” as President Warren G. Harding phrased it. Many women returned to traditional roles and racial inequalities persisted. Soon, however, geopolitics changed once more and America found itself readying for another war.

![Daily Bulletins from the War Zone, [May Craig with servicemen], c. 1944.](/sites/default/files/media/wwii-intro-image1.jpg)

Daily Bulletins from the War Zone: May Craig with Servicemen, c. 1944. Library of Congress

During World War I and II, the government tightly controlled who could be a war correspondent. While women reporters were prohibited from covering the front lines, not all of the 120 or so accredited female reporters followed those orders. Reporter Martha Gellhorn was the sole female reporter to land on the beaches on D-Day after stowing away on a hospital ship headed to Normandy. Gellhorn faced other challenges, including losing her accreditation at Collier’s magazine to her own husband, the famous writer Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway could have easily applied to other newspapers for accreditation and was said to have been upset that his wife had left to cover the war.

Discuss the following questions:

- Why do you think women had to return to more traditional roles after World War I?

- Why do you think Collier's magazine took Gellhorn’s accreditation away and gave it to her husband, Ernest Hemingway?

![Frissell with Europe's Children [Toni Frissell with children], March 1945](/sites/default/files/media/wwii-intro-image2.jpg)

Toni Frissell with children in Europe, March 1945. Library of Congress

Journalist

May Craig defied rules banning women from military planes and warships and covered key campaigns like the V-bomb raids in London and the liberation of Paris. She pushed to get female reporters access to the US Senate galleries and led the charge to have ladies’ facilities installed next to the press gallery. Craig played a leadership role in Eleanor Roosevelt’s all-female Press Conference Association, which the First Lady created in order to push newspapers to hire more female reporters. Years later, Craig pushed to get language into the 1964 Civil Rights Act that extended provisions to women, known as the “May Craig Amendment.”

Female reporters lifted the voices of those often missing from news reports, including women and African Americans. Photojournalist Toni Frissell used her skills as a high fashion photographer to capture and tell the stories of the Tuskegee airmen, an all-Black group of pilots who fought in World War II. Thérèse Bonney used photography to capture the war’s impact on the countryside in her “truth raids.” Her work and awareness were influential in leading the United Nations to create the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) to help children impacted by conflict.

Discuss the following questions:

- What were the contributions of journalists May Craig, Toni Frissell, and Thérèse Bonney during the war?

- How did these women continue to contribute to important causes after the war?

Janet Flanner broadcasting, 1944. Library of Congress

News Format

American wartime journalism included traditional newspaper and magazine reporting, full of photographs that captivated viewers. Photos were often shocking and moving, especially the horrors and displacement of individuals impacted by the Nazi regime and the Holocaust. There was also a new form of mass communication that reached its peak during World War II: radio. The New Yorker’s Janet Flanner produced more than fifty radio broadcasts. Millions of Americans from diverse backgrounds tuned in each day, compared to the 250,000 subscribers to the New Yorker, according to Johanna Cleary in the journal Journalism History.

Margaret Rupli Woodward, who lived in Europe at the start of World War II, recalled NBC News wanting to hire a journalist with an “American voice” that projected. Woodward got the job and produced many reports for NBC radio abroad. “I think basically they couldn’t find a man, and I was available,” she said. Six months later, Woodward fled Holland with her husband after a German bomb hit close to her office. When she tried to get work in the States after the war, she said the NBC editor laughed at her, refusing to even entertain the idea.

Discuss the following questions:

- What was the news format for American journalism during World War II and the impact of photos in newspapers and magazines on readers?

- How did radio’s impact on war reporting compare to the impact of print media? Why do you think there was a difference?