Essential Question

How did a news editor’s or publisher’s point of view affect news reports during the American Revolution and early republic?

Overview

"Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press . . ."

—First Amendment to the US Constitution

Decades before the American Revolution, the British had established newspapers in several major colonial cities. To help the British Parliament communicate with its North American constituents, newspapers freely shared news stories and announcements from Britain and throughout the colonies. This press network later became an important factor in unifying the colonies against Great Britain.

Context

Given the relatively small number of newspapers in colonial and early America, many readers got their news from broadsides and pamphlets, some of which also carried strong Loyalist or pro-independence messages. For instance, supporters of independence and British Loyalists used a wide variety of rhetorical techniques to sway public sentiment in their favor.

Supporters of independence wrote articles using pseudonyms to create the impression that there were many more opponents to British rule than there actually were. Many of the pseudonyms were the names of famous orators of the Roman Republic. The writers who took those names hoped doing so would give credibility to their cause.

While a newspaper’s bias might have been in plain view, this does not mean it supported the idea of “fake news.” Publishers still had to provide credible sources in order to maintain their readers’ trust and their advertisers’ loyalty. Writers sometimes used footnotes if they were unsure about a source.

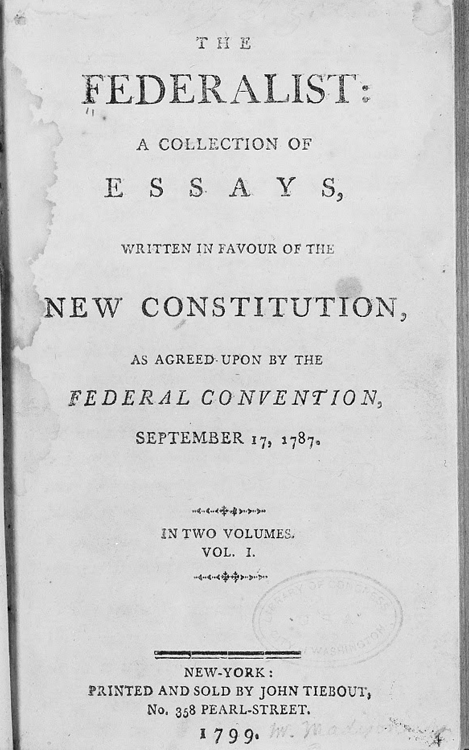

Early Republic

After independence, the country faced economic and political challenges that the limited government couldn’t resolve under the Articles of Confederation. Many sought an expanded role for the federal government to address these and other needs. In 1787, a new constitution was written and sent to state legislatures for ratification. Even before the ink was dry, supporters and critics published their views in newspapers across the thirteen states. Supporters of a stronger federal government were known as Federalists, and those who opposed it were known as Anti-Federalists.

Text Version

"In the press, and speedily will be published, The Federalist, a collection of essays written in favor of the new Constitution. By a citizen of New-York. Corrected by the author with additions and alterations. This work will be printed on a fine paper and good type, is one handsome volume duo-decimo, and delivered to subscribers at the moderate price of one dollar. A few copies will be printed on superfine royal writing paper, price ten shillings. No money required till delivery.

To render this work more complete, will be added, without any additional expence, Philo-Publius, and the Articles of the Convention, as agreed upon at Philadelphia, September 17, 1787."

Although neither the Federalists nor the Anti-Federalists anticipated the development of political parties, these had clearly emerged by the time that John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were contending for the presidency. The Democratic-Republicans boasted their own partisan newspaper, the Philadelphia Aurora, run by Benjamin Franklin Bache and Philip Freneau. In response, the Federalists launched their equally partisan newspaper, the Gazette of the United States.

In the election of 1800, editors took a “no-holds-barred” approach to denouncing the opposition. It would be another forty years before candidates themselves, seen as “gentlemen” in society, would personally campaign for office, and Adams and Jefferson purposefully stayed out of the fray.

Discuss the following questions:

- How did the supporters of independence and British Loyalists each use newspapers to promote their respective positions?

- What role did newspapers play in explaining reasons for or against a strong central government during ratification of the Constitution?

- Describe the early formation of political parties in the United States. How did party leaders use the press to promote their positions?

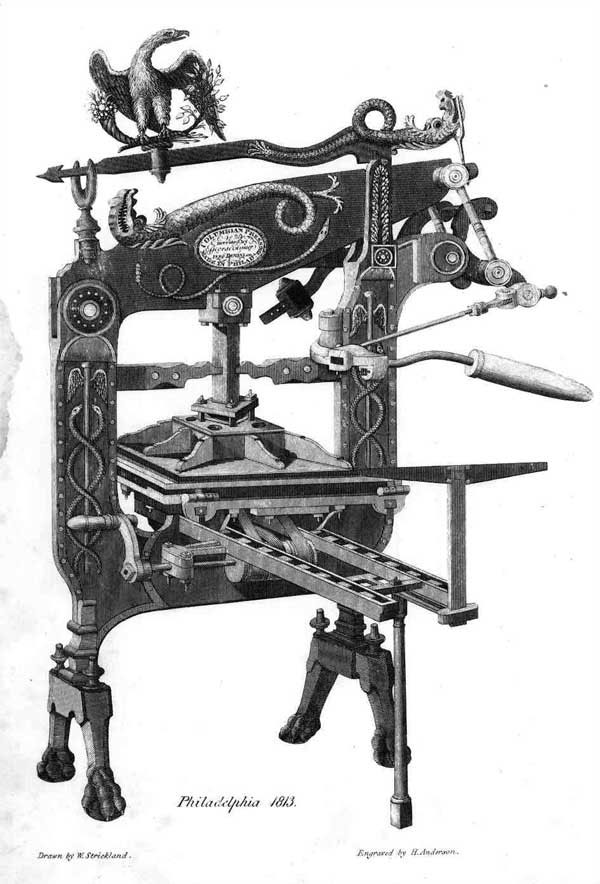

Printing press drawn by William Strickland, Philadelphia, 1813. Library of Congress

News Format

During colonial times, editors filled their newspaper columns with stories lifted from other papers in a practice called “the exchanges.” There were no headlines and few illustrations. Large type was used to grab reader attention for advertisements, not news stories.

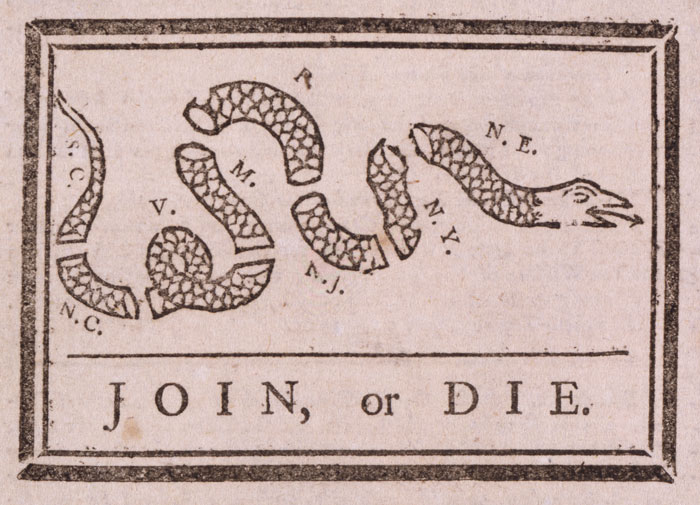

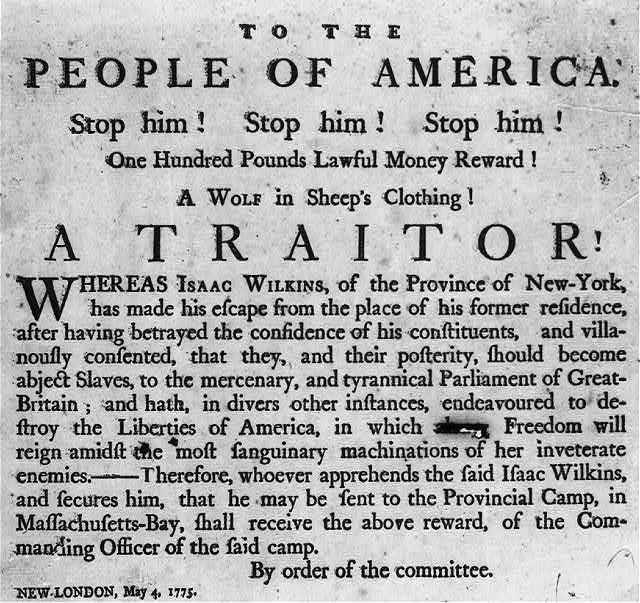

Given the relatively small number of newspapers in colonial and early America, many readers got their news from broadsides and pamphlets, which also used propaganda to carry Loyalist or pro-independence messages. A broadside was a large sheet of paper printed on one side that consisted of announcements, news extras, petitions and advertisements to be posted in public places or shared with others. They were also reprinted and excerpted in newspapers.

Printing costs kept papers small. Most had four pages or fewer. Space was valuable, so news stories contained basic information. Opinion pieces, however, could be rather long and full of sarcasm and bluster. From the colonial period through the revolution and into the first competitive presidential election of 1800, the press experienced enormous freedom, much to the irritation of high officials.

Text Version

To the

PEOPLE OF AMERICA.

Stop him! Stop him! Stop him!

One Hundred Pounds Lawful Money Reward!

A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing!

A TRAITOR!

WHEREAS Isaac Wilkens, of the Province of New-York, has made his escape from the place of his former residence, after having betrayed the confidence of his constituents, and villanously consented, that they, and their posterity, should become abject Slaves, to the mercenary, and tyrannical Parliament of Great-Britain; and hath, in divers other instances, endeavoured to destroy the Liberties of America, in which Freedom will reign amidst the most sanguinary machinations of her inveterate enemies.—Therefore, whoever apprehends the said Isaac Wilkins, and secures him, that he may be sent to the Provincial Camp, in Massachusetts-Bay, shall receive the above reward of the Commanding Officer of the said camp. By order of the committee.

NEW-LONDON, May 4, 1775.

Discuss the following questions:

- What were the different forms of news sources during the colonial period?

- Look at the example of a broadside above. In what ways does the publisher try to draw the attention of the reader with words, font size, and statements?

- Read the description of news media from the colonial period to the election of 1800. How was the news media then similar to the news media today?

Journalists

Newspapers were the main published sources of news and provided information on a variety of subjects. Pamphlets were usually focused on one topic or issue. The writers of these publications might not be recognizable as journalists by some of today's criteria. Standards of truth, fairness, and accuracy weren’t always evident. In fact, many editors openly showed bias and took sides on the issues or candidates, some using distortions, character assassination, and rumors to promote their point of view.

Boston businessman and patriot Samuel Adams was one of the most influential advocates for the American Revolution, both in print and in person. Adams’s Sons of Liberty and the Boston Gazette were very skillful in crafting the message that British rule was akin to slavery. Fellow Sons of Liberty member Paul Revere purposefully adjusted the facts to fit the message he wanted to convey in his engravings. Revere’s famous engraving of the “Boston Massacre” was repeatedly printed in papers and pamphlets throughout the colonies and was seen as a call to arms.

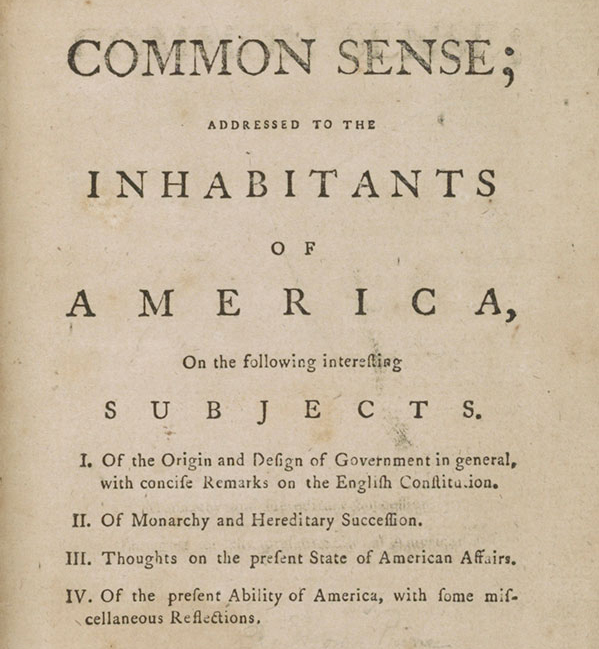

One of the most famous and radical pamphleteers was Thomas Paine, an English-born immigrant who came to the colonies in 1774, just as things were heating up. Paine articulated the ideological justification for independence in publications like Common Sense and The Crisis. “By which the world may know that so far as we approve of monarchy,” the Paine wrote, “that in America The Law Is King."

While most journalists during the Revolutionary War were white men, women played key roles as writers and newspaper publishers. Playwrights like Mercy Otis Warren wrote thinly veiled satires that attacked British officials, which appeared as serials in newspapers.

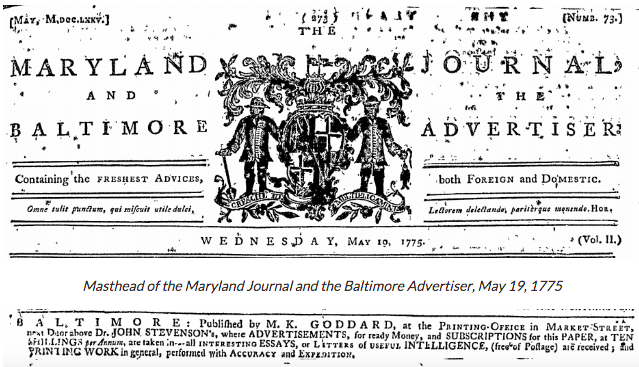

Maryland Journal and the Baltimore Advertiser, May 19, 1775. Edited to include both masthead on the top portion and publisher’s name on the bottom portion. Permission has been granted for educational purposes only by the New York Public Library.

Publisher Mary Katharine Goddard played a key role in the Revolutionary War era, editing impassioned articles, including her own account of the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. One letter to the editor stated that “a British parliament has no more right to tax an American in anything than they have the right to tax the people in Japan.” Goddard was most well known for printing the first copy of the Declaration of Independence, which featured the signers’ names—as well as her own—a bold move, as it was an act of treason for all involved.

Discuss the following questions:

- How did journalism standards during the early republic differ from today’s standards?

- Describe how patriots like Sam Adams used the aspect of slavery to criticize British rule over the American colonies. Considering how prevalent slavery was in the colonies, why is this ironic?

- Who were some of the women who used the press to promote independence? Explain how their contributions to the press were courageous. What did they have in common with the Sons of Liberty?