Essential Question

How have journalists covered gender equality in ways that show the challenges and successes of the women’s rights movement?

Overview

Gender discrimination and the fight for equal rights have played a significant role in shaping American society.

In this case study, you’ll analyze coverage of women’s rights and explore how people have used media to bring attention to their causes. Issues that affect women of color and low-income women, who have faced higher levels of discrimination and have been historically left out of women’s rights campaigns, will also be examined.

Context

When the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776, no mention was made of “women” in its famous opening: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

At the time of the formation of the US Constitution, women did not have the right to vote, hold political office, or serve on juries. Enslaved Black women had no political rights and little legal recourse to address harm done to them.

While legal rights for women in the early US broadly reflected European attitudes at the time, not all contemporary power models granted political enfranchisement only to men. Benjamin Franklin championed the Haudenosaunee’s Great Law, or “Iroquois Constitution,” as inspiration for the Articles of Confederation. Women had long held political power among the tribes of the Haudenosaunee federation, which stretched throughout what is now New York State and beyond.

It would take hundreds of years for women who were US citizens to achieve some of the legal and political rights of Haudenosaunee women. Much of that struggle was played out in the pages of printed newspapers, women’s magazines, and, eventually, the Internet and social media.

Discuss the following questions:

- What main idea about women’s rights were Life’s editors attempting to make in their cover illustration?

- Why do you think it took so many centuries for women who were US citizens to gain the same civil and political rights as men?

News Format

Women’s Magazines and Newspapers

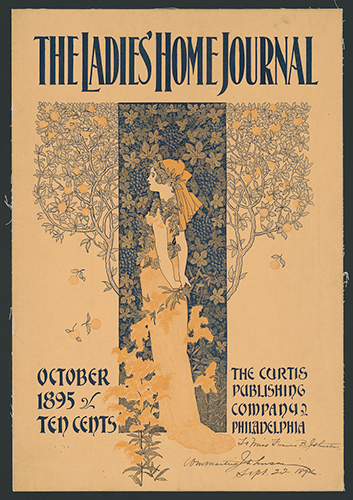

During the nineteenth century, American “women’s magazines” or the “women's page” of newspapers were dedicated to covering news deemed to be of interest to predominantly white middle- or upper-middle-class women.

Magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Vogue, and Cosmopolitan were criticized for covering “trivial” subjects such as cooking, decorating, and fashion, but they also published women’s voices missing from the larger publications. Many women including famed investigative reporter Nellie Bly got their start as journalists in these pages.

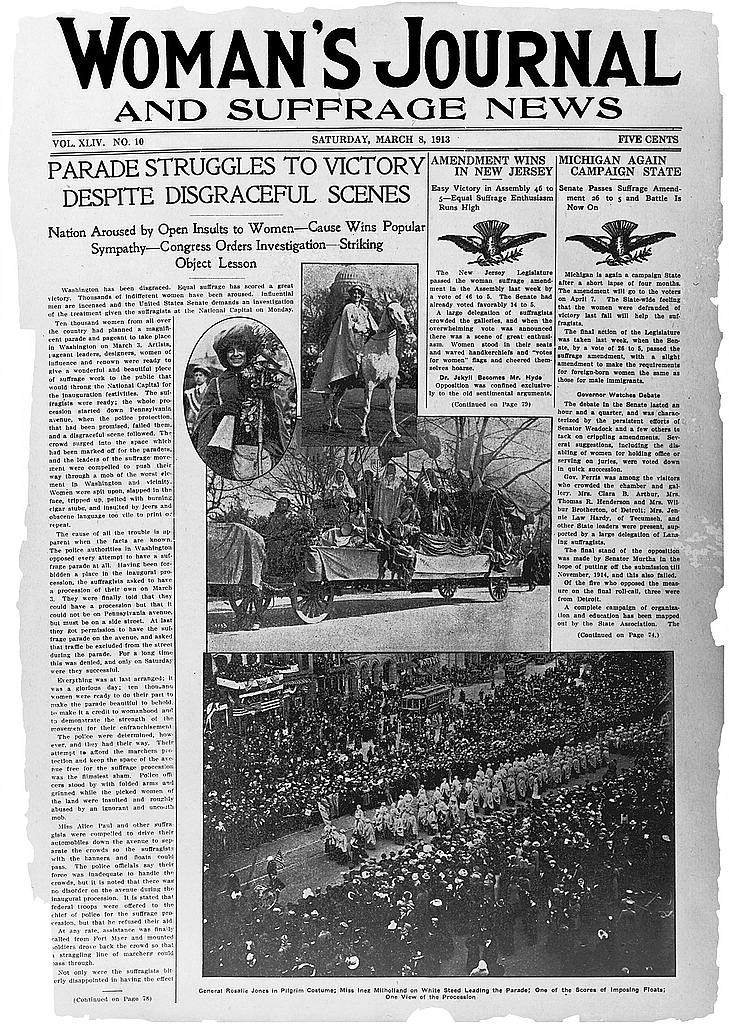

Alice Stone Blackwell, editor-in-chief of the Woman’s Journal, covered the 1913 women’s suffrage parade in Washington DC, the largest parade held in the nation’s capital up until that point. The parade was widely covered by newspapers across the country.

Suffragists who were not journalists often knew how to attract attention to their cause, including the “Suffrage Pilgrims” who made a 295-mile trek from NY to DC, and were the subject of local news stories along the way. Still, women’s magazines mostly lacked the perspectives of non-white women.

One important news story left out of most newspapers had to do with the issue of segregation of African American women who were instructed to march towards the back of the parade. Suffragist and investigative journalist Ida B. Wells ignored the rule and famously marched at the head of her state’s delegation. Wells was an established journalist and national figure, even though her work was relegated to the Black press.

Although the Nineteenth Amendment succeeded in granting women the right to vote, it would still take the effort of many generations of activists and journalists to achieve greater representation for women in politics and news.

Discuss the following questions:

- From what parts of society were women able to have their voices heard in major national newspapers or magazines?

- What do you think the effect was of women journalists communicating directly to readers about the suffrage movement?

Journalists

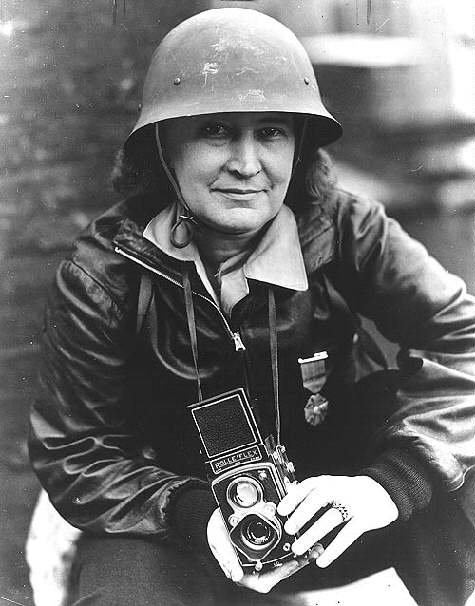

Women journalists served throughout the twentieth century covering war and politics; however, not in the same numbers as men, mirroring representation of women in other professions. To learn more about women war correspondents during World War II, be sure to check out our case study on this topic.

During the post-war period, women continued to cover news of the day in both newspapers and magazines as journalists and—in rare cases at first— as media executives. In 1963, Katharine Graham took over leadership of the Washington Post, a paper that had been owned by her father. Under Graham’s leadership, Washington Post journalists exposed many details of the Watergate scandal (this episode is covered in the Watergate case study).

Women also began to found a new generation of women’s magazines, which took on a place of prominence in the 1970s and addressed controversial political and cultural issues of the day.

Ms. magazine was based on the ideas of the women’s liberation movement. Gloria Steinem, a co-founder of Ms., was one of the most well-known leaders of the feminist movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Essence, which also debuted in 1970, centered on Black women’s successes in business, fashion, and the home and became the fastest-growing magazine at the time.

Even as women took on more prominent roles in national media, their voices remained a small fraction of that of male journalists. This was especially true with television broadcast news, where a great majority of broadcast television anchors and correspondents were men well into the twenty-first century. In 1960, Nancy Dickerson became television’s first national broadcast journalist for CBS. She was also an associate producer of Face the Nation and later reported for NBC News.

Other women journalists including Leslie Stahl, Ethel Payne, Barbara Walters, Connie Chung, Diane Sawyer, and Katie Couric became household names throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Still, by the turn of the 21st century, women’s voices were underrepresented on television and in print. It wasn’t until 2013 that two women, Judy Woodruff and Gwen Ifill, co-anchored a national evening news broadcast for the PBS NewsHour for the first time in history.

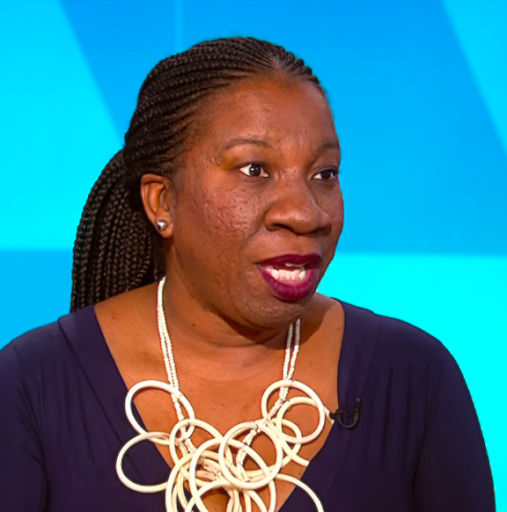

With the advent of social networks around 2000, millions of people were able to speak out on topics of the day, including commenting on issues that traditional media had been reluctant to address. “Citizen journalists” have used the web to publish their own news stories that sometimes took on a different focus than national media. Activists and citizen journalists helped launch movements such as Black Lives Matter and the #MeToo that were then picked up for coverage by print and television journalism.

Tarana Burke founded #MeToo as a way to include stories of women of color and low-income women whose voices had been historically left out of social movements and media coverage. Women and some men began to share their own stories of sexual harassment and assault on Twitter using the hashtag #MeToo. The #MeToo movement contributed to investigations of media figures such as Matt Lauer and Charlie Rose who had been accused of sexual misconduct. In this way and others, citizen journalists have helped reshape the media landscape.

Discuss the following questions:

- How does hiring journalists from diverse backgrounds (race, class, gender, disability, sexuality, etc.) affect news coverage?

- How have citizen journalists used the Internet, including social media, to engage in debates and gain attention for causes they care about?